HOW to sell cars when most people can’t afford to buy one?

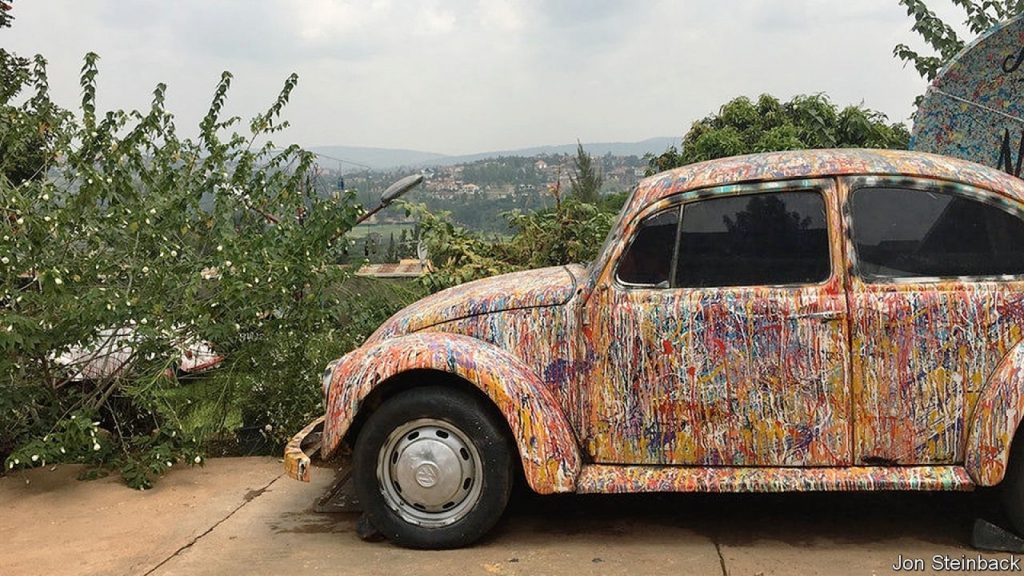

That is the conundrum for Volkswagen in Rwanda, where it is opening the country’s first car-assembly plant. A new Polo costs 33 times the average Rwandan income. Most cars on the road are second-hand imports. Rwanda absorbs perhaps 3,000 new cars a year, says Thomas Schäfer, VW’s chief in Africa. Past projects by carmakers in Africa, he admits, have ended in “monumental failure”.

Yet there was a hopeful mood when VW launched its operations in Kigali, the Rwandan capital, on June 27th. The moment opens ”a new chapter in Rwanda’s journey,” said Paul Kagame, the president, after taking a demonstration model for a spin.

In truth, little of the manufacturing will happen locally, at least to begin with. VW will build its vehicles elsewhere, partly dismantle them, then put them back together in Rwanda.

The real novelty is how the cars will be used.

VW is linking production to a ride-hailing and car-sharing service, stocked with its own vehicles.

More people will pay to use a car, it reasons, than can afford to own one. At first, firms and government agencies will be able to use shared vehicles; from 2019 a similar service will be rolled out to the general public, with cars stationed around the city. Anyone with the mobile app will also be able to call up a lift, starting this October. The cars will be used for a few years, then sold into the second-hand market. The $20m project will initially produce 1,000 vehicles, with capacity to churn out 5,000 units a year.

Kigali is a small, orderly place in which to test the idea. If it works, VW could replicate it. It has recently restarted assembly in Kenya and Nigeria, after decades away, and hopes to enter Ghana and Ethiopia. Mr Schäfer likens VW’s African ambitions to its decision to enter China in 1985. At the time, Chinese car-ownership rates were lower than in most African countries today. Now, VW sells over 3m passenger cars a year there.

Some help comes from African governments, which shield producers from competition. Kenya plans to lower the maximum age for imported vehicles, from eight years to five. Nigeria imposes tariffs of up to 70% on car imports. Yet protection is often patchily implemented.

For now, cautious carmakers are edging along in first gear.